Varicocele

Felice D’Antuono MD

VARICOCELE IN MEN

A varicocele is a vascular lesion characterized by dilatation and tortuosity of the spermatic veins. It is commonly found in adolescents and young adults. Varicocele is found in approximately 15% of adult males, but the incidence could go as high as 40% in patients attending infertility clinics and up to 80% in those with secondary infertility. Varicoceles predominantly affect the left side (90% of cases) with bilateral varicoceles present in 10% of patients. Varicoceles can be primary or secondary to increased pressure on the spermatic veins. Secondary varicocele is usually manifested on the right side.

Mohammed A, Chinegwundoh F. Testicular varicocele: an overview. Urol Int. 2009;82(4):373-379. doi:10.1159/000218523

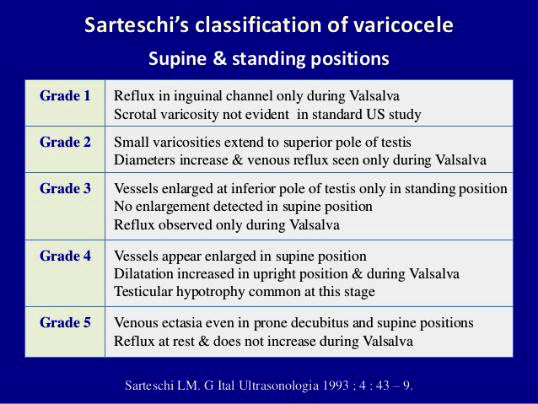

Ra diologists can not only perform diagnoses with ultras ounds, thus classifying the condition as Grade 1 or 2, which is all but asymptomatic, but can also treat it when it becomes symptomatic. It can cause pain and infertility and it can be treated either surgically or with embolization.

Embolization is a widely accepted treatment for varicocele: the first reported attempt dates as back as 1978 when Lima et al. induced sclerosis by catheterization of the internal spermatic veins with the injection of a 75% hypertonic glucose solution. Later, in 1981, Formanek et al describe bilateral embolization using a transjugular approach.

Treating varicoceles using an endovascular, percutaneous approach is quite easy: we usually prefer to puncture the right femoral vein (whereas other colleagues would rather enter the jugular or the basilic vein), then perform a phlebography and catheterize the left testicular vein. Our target is the anterior pampiniform plexus, which is drained by the internal spermatic vein because this is where the pathology originates. Correct treatment will avoid relapses. We select the left renal vein with a 6-Fr guiding catheter, then perform a renal phlebography and easily locate the left spermatic vein. With a hydrophilic guidewire and a 4-Fr sheath, we select the vein. Due to the wide range of anatomical variances, the phlebography plays an important role in this procedure: we need to ascertain whether we have one or two collectors, for instance, or if there is evidence of anastomosis involving the lumbar vein. Distal catheterization is usually performed with a 4-Fr catheter or, in particularly difficult cases, with a microcatheter. We inject the glue gently, making sure it does not migrate to the plexus because this might cause thrombophlebitis.

Alternative ways to treat varicocele percutaneously include coils, sclerosants, or other embolic agents, and the available literature on the use of glue in this setting is still insufficient. Nevertheless, an interesting 2017 systematic review from the UK analyzed the different materials and reported the following conclusions: “Despite the heterogeneity of the included studies, preliminary evidence supports the safe and effective use of the various embolic materials currently used for the management of varicoceles. At 1 year, glue appears to be the most effective in preventing recurrence with coils being the second most effective. The addition of sclerosants to the coil embolization did not appear to have an impact on recurrence rates. Further research is required to elucidate the cost-effectiveness of these approaches. Advances in knowledge: Varicocele embolization appears to be a safe and effective technique regardless of the embolic agent. Addition of a sclerosant agent to coil embolization does not appear to improve outcomes.”

Makris GC, Efthymiou E, Little M, et al. Safety and effectiveness of the different types of embolic materials for the treatment of testicular varicoceles: a systematic review. Br J Radiol. 2018;91(1088):20170445. doi:10.1259/bjr.20170445

Our team at Humanitas also ran a study to report a 3-year experience in varicocele embolization using n-butyl cyanoacrylate¬methacryloxy sulfolane (NBCA-MS).

We retrospectively collected data from 47 procedures [mean age = 27.9 years, SD=8.3], selecting candidates according to the following criteria:

Inclusion Criteria:

Diagnosis of Varicocele:

- Urological or Radiological Diagnosis (Clinical Visit and Coior-Doppler US)

Exclusion Criteria:

Pain from:

- Testicular torsion

- Epididymis

- Orchitis

- Inguinal hernia

- Recent trauma

OUTCOME MEASURES:

- Length of Procedure (through electronic records)

- Impact on groin pain (4-point scale through telephonic contact)

- Complications (CIRSE Classification System)

- Recurrence Rate

- Patient Satisfaction (4-point scale through telephonic contact)

- Spermiogram Changes (sperm count; percentage of motile or normal morphology sperm)

Pain improvement was evaluated using a 4-point scale:

- Mild pain

- Considerable pain

- Severe pain

- Unbearable pain

RESULTS

- 43/47 left-side

- 3/47 bilateral

- 1/47 right-sided

— Procedures were technically successful in all cases

— Mean length of procedure was 42 minutes

— Follow-up was 18 months (range=1-83, SD=17)

— 40/47 (85.1 %) patients completed the questionnaire regarding late post-procedural pain and overall satisfaction towards the procedure

RESULTS – Pain improvement

- 26/40 (65%) patients were symptomatic before the intervention

— 08/40 (20%) patients felt discomfort (1 point)

— 05/40 (13%) patients felt mild pain (2 points)

— 10/40 (25%) patients felt considerable pain (3 points)

— 03/40 (7.5%) patients reported unbearable pain (4 points)

- Pain score decreased significantly from an initial mean of 1.5 (SD=1.4) to 0.4 (SD=0.5) p = 0.0001 (mean reduction 73%)

–16/26 (62%) patients reported complete disappearance of varicocele-related symptoms

— 9/26 (35%) patients reduced or halved the initial pain

— only 1 patient reported a pain decrease <50%

RESULTS – Spermiogram changes

- 34/47 (72%) patients underwent varicocele embolization after a baseline spermiogram

- only 18/40 (45%) patients underwent a spermiogram after the procedure

- 16/18 (89%) patients reported an improvement in spermiogram values either in sperm count or in motile/normal morphology sperm percentage

Two patients (11%) did not report any improvement. Post-procedural spermiograms results were stable in one case, worse in the other.

RESULTS – Complications

No major complications were observed.

- Scrotal pain was observed in 3/40 (8%) patients immediately after the procedure. At 1-month follow-up, pain had disappeared completely

One patient (27yo) with severe bilateral varicocele suffered from a small, non-target embolization in the left pulmonary artery. However, the incident had no consequences and the patient was completely asymptomatic for the entire time.

VARICOCELE IN WOMEN

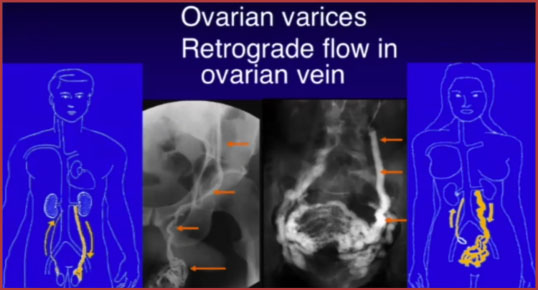

The gonadal veins are paired structures that drain the gonads in males and females. In males it is called the testicular vein (or internal spermatic vein) and in females it is called the ovarian vein. The gonadal veins ascend with the gonadal arteries in the abdomen along the psoas muscle anterior to the ureters. Like the suprarenal veins each side drains differently:

— the left gonadal vein drains into the left renal vein

— the right gonadal vein drains directly into the inferior vena cava. Gonadal vein-Radiopaedia

Incompetence and retrograde flow in the gonadal veins can result in a varicocele in the male and pelvic congestion syndrome in the female. Venography and therapeutic embolization of incompetent gonadal veins are performed on male and female patients for different clinical situations using similar techniques.

Bittles MA, Hoffer EK. Gonadal vein embolization: treatment of varicocele and pelvic congestion syndrome. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2008;25(3):261-270. doi:10.1055/s-0028-1085927

When we talk about varicocele in women, the situation appears completely different:

- CCP (Chronic Pelvic Pain): continuous or intermittent noncyclic pain of 6 or more months’ duration

- 10% -> general population

- 30 – 40% -> PCS or PVI (pelvic congestion insufficiency)

- PCS (Pelvic Congestion Syndrome): when varicose veins develop around the ovaries in a CCP setting, causing pelvic pain with no other identified cause.

- Sometimes, vulvar/labial/ perineal varicosity

- Typical difficult patient: multipara, 40-50 yo with multiple previous pregnancies, with chronic pain, generally bilateral or left-side prevalent, often exacerbated by prolonged standing, coitus, menstruation, and pregnancy

- Rarely: hip pain, lower extremity varicose veins, persistent genital arousal

CASE REPORT

47yo woman; Non-smoker; previous spontaneous PNX; Since November 2018: dysuria then pelvic and perineal pain; Antibiotics with no improvement; Since January 2020: dysmenorrhea, severe pain before and after menstrual cycle; Urological evaluation: negative; Gynecological evaluation: negative; Suspect PCS

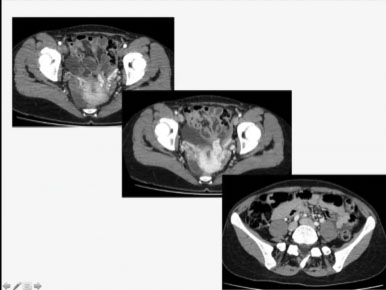

MDCT arterial phase image revealed early opacification of the periuterine plexus and congestion of both left and right gonadal veins. The symptoms were consistent with PCS and the patient was, therefore, eligible for percutaneous treatment. We proceeded as per angiographic evaluation but, when we got to the jugular vein to catheterize the hypogastric axis and the uterine vein to assess the situation, we decided to place an occlusion balloon and gently inject a 2:3 Glubran®2/Lipiodol mixture into the vessels. For the right ovarian vein, we opted for a 1:2 ratio, as the situation appeared more manageable.

- Glubran®2/Lipiodol 2:3 ratio, 2ml for left ovarian vein

- Glubran®2/Lipiodol 1:2 ratio, 1 ml for right ovarian vein

- Procedure length: 55’

- No complications